|

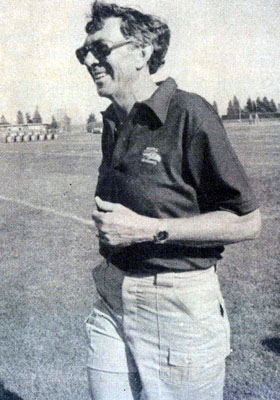

Herman Sarkowsky

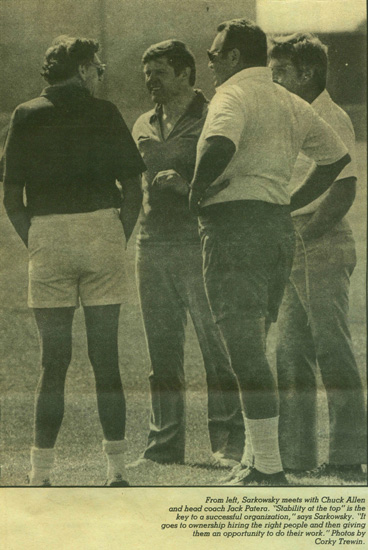

Thoroughbreds to Blazers to Seahawks, Herman Sarkowsky is ‘stability at the top’By Pat DawsonSource: Norm Evans' Seahawks Report, Oct. 29 - Nov. 4, 1979 In 1977, the National Basketball Association team he founded, trailing two games to none in the best-of-seven world championship series, staged an incredible comeback against Philadelphia to win the league title. Two years earlier, his champion Thoroughbred won two major stakes races at Hollywood Park, America's biggest race track. And in 1978, the National Football League club he serves as managing general partner produced the best third-year record in league history. He is Herman Sarkowsky, a 54-year-old former home-building entrepreneur, who, by any count, must rank as the first sportsman of the Northwest. That Sarkowsky has built a sports empire of sorts should come as no great surprise. United Homes, a company Sarkowsky began and expanded down the West Coast, was eventually purchased by ITT. The analogy between the two enterprises seems obvious: construct a solid foundation and the structure will endure. Admittedly, however, when Sarkowsky first organized the Portland Trail Blazers, the two-by-fours splintered. "We did everything wrong," Sarkowsky recalled of his pro sports debut. "Harry Glickman, the general manager, really put the deal together. Neither of us had any experience in basketball. We compounded that weakness by hiring a director of personnel who had never been in the NBA, who then helped us select a coach who had never been in the NBA, who helped us select other people who had no NBA experience." Profit? Five years later, the Blazers acquired Bill Walton, and, within a year's time, sold every seat in Memorial Coliseum. Today Sarkowsky orchestrates what many observers feel to be the best-run franchise, along with the Dallas Cowboys, in the best-run league in professional sports. When Sarkowsky and partners laid the Seahawk foundation the concrete was personified in general manager John Thompson, head coach Jack Patera and a staff Thompson pruned from throughout the NFL. At the time the Seahawks were conceived on paper, Dick Vertlieb, the former general manager of the NBA champion Golden State Warriors, was asked to present a pro forma. Vertlieb placed Thompson's name at the top of the management team. "I interviewed other people," Sarkowsky said, "but never seriously considered other people." With Thompson in the fold, the search for a head coach began in earnest. Patera had written Thompson, requesting an interview. He was the last of four finalists to be interviewed, following Leeman Bennett (head coach, Atlanta), Marv Levy (head coach, Kansas City), and Monte Clark (head coach, Detroit). "John and I flew to Minnesota and interviewed Jack," Sarkowsky explained. "We had interviewed all the others twice, but this was our first talk with Jack. There was something about him. Afterwards, I said `that's our guy.' Of all the people we interviewed, my reaction was that that's the guy we want. John agreed." What Sarkowsky saw in the former Minnesota line coach was a combination of ingredients. "The way he answered questions, his philosophy about the game," Sarkowsky listed as particularly attractive. "Stability, a tendency not to get overemotional, which I think is important when you're dealing with a lot of young people of questionable talent the first couple of years. Leadership qualities, the ability to make good staff decisions. And a certain charisma was apparent to us," Sarkowsky continued. That Sarkowsky and five other prominent Seattle businessmen (Ned Skinner, Howard Wright, Lloyd Nordstrom, Lamont Bean and Lynn Himmelman) were even in a position of ownership in the NFL is a testimony to that group's inspection before the league. The franchise was first awarded to the city, then specifically to its present ownership in 1975. The lengthy acquisition process began four years prior in a conversation between Sarkowsky and Skinner. Sarkowsky mentioned that he had been approached about locating a National Hockey League franchise in Seattle, but wasn't interested. What both men were interested in was local ownership of an NFL team. "We went through a list of names," Sarkowsky recollected. "We were convinced our group should consist of no more than six people. We had a series of luncheons and brought together people we thought we could live with over time. To the latter condition, Sarkowsky advises, "sports bring out strange emotions in people." The original concept was that Sarkowsky would purchase 51 percent, but the all-time low in the stock market and the high price ($16 million) of the franchise dissuaded him. The Nordstroms, the Hawks' majority owner, were the last to enter into the partnership. Lloyd Nordstrom was interested only in becoming another partner. But when the league awarded the franchise and began to interview prospective ownership groups, a 51 percent entity was required. Nordstrom and clan agreed to a majority position, thus solidifying the group's eligibility and custody of the Hawks. Four years later, the partnership remains intact. "I can tell you from my observations," Sarkowsky perceived, "that it's been a beautiful, beautiful arrangement." While Sarkowsky is the most active of owners in the club's business, he feels "the others are as involved as they want to be. What I contribute is in the area of counseling in the business aspects of the operation." And business, for the Seahawks, has been brisk. Virtually every seat is sold for the 1979 season, following the heels of 11 sellouts in the club's first three years of existence. The product has been a winner, if not in the standings certainly in style, from day one. "We wanted a team that maybe didn't win, but certainly looked like it had potential," Sarkowsky advised. "One that the fans enjoyed watching, even when we lost." But winning was discussed, albeit in muted tones, in the Hawks' earliest days. "At the end of five years, we wanted to be on a par with other teams," Sarkowsky remembered. "We might not be as good as the top teams, but we certainly wanted to be better than the average teams. The plateau for us at the end of five years was .500. When you reach that plateau, then you have the talent to reach the next plateau—the playoffs. The difference between a team like ours today that was 9-7 last season and 10-6 is not very much." That the Seahawks nearly reached the summit in 1978 was a direct reflection on Thompson and his management team, and the ownership's deft hand at landing Thompson the NFL Executive of the Year. "Stability at the top," Sarkowsky suggested as the key. "It goes to ownership hiring the right people and then giving them an opportunity to do their work. I probably know more about the least successful teams in the league than I do about the successful ones. I think you learn from the guys who do everything wrong. I know what went wrong in New Orleans, Houston and other clubs. Mostly, it was a combination of things, probably ownership's inability to pick the right people, if you could capsulize it." That rival clubs now study the Seahawk ownership is no secret. “Herman is probably one of the most influential owners in the league," an associate commented. "He is certainly the brightest." That professional sports entrepreneurs are becoming more sophisticated, more involved in their clubs today, is easily explained. Pro sports, once the rich man's toy, now adds to the riches. "When we bought the Seahawks, we considered it a mediocre investment," Sarkowsky related. "It is better than that now because of the increase in television revenues. Also, we have exceeded our projections in terms of attendance." But television remains the single most important factor in sports biz today. Revenue, in most stadiums, is limited by the number of seats and the dollars one can reasonably charge to fill them. Player’s salaries, insurance premiums, etc... have accelerated past the inflation rate. "I don't know how long TV revenues will continue to rise, but that's one thing that keeps football franchises viable," Sarkowsky said. "To my knowledge, not a single professional sport can exist on ticket revenue alone. Forty to 50 percent of our revenue comes from the media."

It is also Sarkowsky's belief that football, unlike other pro sports, enjoys a special love affair with the tube. "I think pro football, as played in the NFL, is the only game that is accepted nationally. Whether it's Sunday afternoon, or Monday night, people will watch the game, regardless of who's playing. Basketball is parochial. People won't watch Seattle-San Antonio, but people in New York will watch a Seattle-Atlanta Monday night football game." What keeps football at the top of the standings in the Nielson League, Sarkowsky suggests, is the spectacle of the game. "Football is more of a happening," he believes. "In basketball, the object is to get there right before tip off and leave as soon as the game's over. When we go to a Husky game, we start at 10:30 with a Bloody Mary, have lunch somewhere and do something afterwards. The Seahawks only have 11 (home) games, so you have a bigger buildup," he explained. What, then, of the danger of saturation? Four clubs have been added in the past 13 years, the regular season increased by two games a year ago, and the number of weekly broadcasts from one to as many as three this season and last. "I don't think there can be an over-saturation of football unless they play every night. People look forward to Monday night games. Thursdays (scheduled four times this season) will be popular also, I think. I can see a ceiling on teams: not more than 30, six divisions of five each. Any expansion past that should be international." Despite the ownership-management position Sarkowsky holds, he remains, by his own admission, the quintessential fan come game day. That he is joined by 60,000 screamers is his delight. "You can't watch a game dispassionately," Sarkowsky asserted. "Even the guys who cover from the media—I've accused them of being fans. I've watched their reactions." He had also watched the demeanor of athletes on his teams and opponents'. In basketball, particularly, he finds that some emotion oftentimes is lacking. "It's very tough to get excited about (Kareem Abdul-) Jabbar. I know that he cares about the game, that he likes to win. But people who watch him don't know that. (Bill) Walton was much more demonstrative. The Sonics were emotional on the court." There can be no doubt that Sarkowsky "gets up" for Sundays in the dome. "Someone once asked me," he related, "what would be the more exciting to me: the Kentucky Derby, or the Super Bowl. At the time I said the Derby. But I've kinda changed my mind."

|